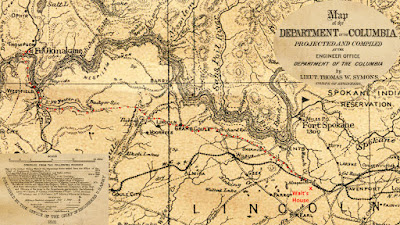

Wagon trails that vanished by never turning into roads were once common in Lincoln County. This was before surveyors made wandering people stay on section lines. Early settlers and explorers took the path of least resistance by just looking ahead, then aiming their teams between the sagebrush, and telling the horses to get going.

There are a number of early day stories about trails that do not have an author. The Mosquito Springs Trail is well documented, so is worth reciting.

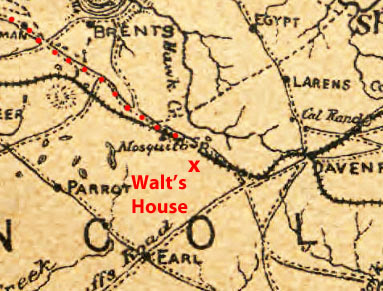

This wagon-freighting trail went past our back porch. (Yes, part of our house is that old.) This trail came out of Cottonwood Springs, now Davenport. It went west for five miles. Then the wagon tracks curved northwest for another five miles to Mosquito Springs, so named because old-timers found lots of mosquitos living there. The trail then stretched its way to [Fort] Okanogan.

A sprouting freight company figured this cool spring would be an ideal spot to exchange horses. There was lots of knee-high virgin grass growing all around this typhoid-free watering hole, just waiting to be chewed off. The company erected a good-sized cabin, including a fireplace made from rocks that were just laying around there.

A guy was hired that understood horses, and his job was to jump out of the cabin when a freight wagon arrived from either direction. He would strip the tired horses of their pulling outfits, while the wagon skinner would usually stretch his legs, take off his hat, and bend over the spring for a cool drink.

Each animal’s front legs were then hobbled, making it possible for the horses to fall flat on their faces if they tried to run away. The poor dears soon learned to eat the bunch grass that was there and to be ready to do more pulling when the next exchange string of beasts arrived at this rest stop.

The first guy that was hired to occupy this lonely post was known as the “Squaw Man”. After a few weeks he got tired of swatting mosquitos and started hankering for a squaw. It didn’t take him long to run off with one, and he eventually settled around the Okanogan country where he started a family.

These old freighting wagons that went by Mosquito Springs were called high-wheeled wagons. Their axels came equipped with tall, narrow wheels, making road clearance out of this world. They were designed to slip-slide around rocks much better than the usual wide, squatty-looking wheels that came with the later flatbed wagons. The back wagon got its steering tongue amputated to half length, so it would follow better when it was hooked on back of the front wagon.

Business was neat while it lasted. The brand new settlers along the way needed sow belly (bacon) and lots of flour to make all the sour dough bread they could eat.

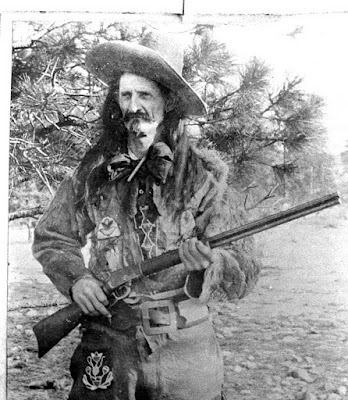

Of course, these wagons carried other stuff that wasn’t needed tor the stomach and occasionally would pick up a wanderer that happened to be horseless. One such fellow who was dressed like a dude asked for a ride. The wagon master soon found himself listening to the vagabond’s account of how the government rewarded him for cleaning out all the hostile redskins that were hiding in the Dakota badlands. He claimed he was known as “Death on the Trail", because of his renowned ability of tracking down these bad Indians and eradicating them.

After leaving the supply wagon at Bridgeport, old “Death on the Trail” was wanted for selling “firewater” to the Spokane Indians and was soon picked up by the Feds from Fort Okanogan.

Who were the outdoorsmen that drove these rigs? The two main guys were the Brink boys. Milo, the oldest, was a colorful, early day territorial character with a long-handled mustache who, as a lad of 18, rode the grasslands between Cottonwood Springs and the Moses Coulee for Barney Fitzpatrick, Davenport’s pioneer cattleman.

When a handful of investors put together the Big Bend Freight Company, Milo and his brother Bill were hired to drive those cargo hauling wagons to Okanogan and back. For a short time the company got a contract to haul freight and passengers to Fort Spokane. Bill then got transferred.

They used a real stagecoach for this run. It had lots of room on top to tie down things the Fort bosses wanted. This route lasted until the government decided that the local Indians didn't act or look very dangerous. The soldiers soon left to where people were making more fuss.

Milo’s daughter, Roxie Nichols, recalls vividly when as a girl of 12 she went with her uncle on his last run to the Fort. She excitedly sat next to him where the brake lever and the lines were located. Bill’s last load consisted of fare-paying Indians that rode down in the enclosed hatch. Riding in the back, laying in a lump, was a tied-down Fort order of sugar and flour, also a case of Davenport’s own brand of homemade lye soap.

When the horse-powered, fresh-aired freighting days ended, Bill got to be a U.S. Marshal and was sent to California. Milo, years later, took a job as deputy sheriff for Lincoln County. Time buried the Brink boys, and the settlers’ plows buried their trails. However, some of their trails are still visible on the scabland in section 22, range 36.

"Wagon Trails" Kik-Backs, page 18 (home) (thread)

Comments

Post a Comment