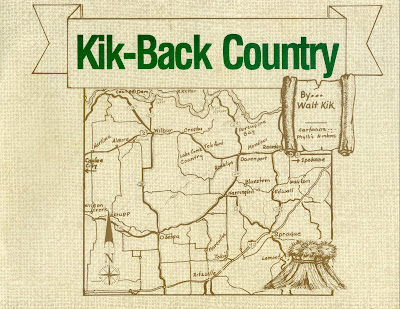

Kik-Backs

By Walt Kik, edited by Phil Krogh

Chapter One

I was born at least 40 years too soon. I believe the young folks now days have a much better chance of finding themselves than when I was a young guy. The new generation is asking questions and expecting answers. They live in a more enlightened world. But things were different in my "B.S." days (before Sugar). You were expected to remain a dumb cluck until somehow you found the right girl. Then after the marriage vows, you were supposed to have instant knowledge of the whole darn works of life and live happily ever after.

When I got old enough to shave, all I could think about was how to raise wheat instead of heck. But as time passed, even a field of waving grain couldn’t hold my attention all of the time. Soon I could hardly wait until Sunday came around to join the ball team that played down in Lybecker’s flat. There were girls there watching us guys play ball. I got down there too late to join the courting rat-race. All the girls were paired off and going steady with sprouting future farmers. That left me, all alone with my Model T, a jar of peanut butter, and no place to go after the game.

Fortunately (or unfortunately, depending how one looked at it), a break came for me to explore beyond my stomping grounds. Because of hard times, I went into partnership that harvest season with O.J. Maurer. Needing help, we hired a rounder that went by the initials of C.P., alias Windy Anderson, alias Battling Gunboat. His left leg was three inches shorter than the right one. He claimed that at one time he was the middle-weight boxing champ of the Navy. His success came because he could pivot so fast on his short leg that his opponent didn’t know what happened as he nailed him.

C.P. claimed he was God’s gift to women and stated he had just attended the dance out at the North Star Grange where he got acquainted with a couple of beauties. It was a tough night, he said, as he had to make a cruel decision as to which girl he should take home. Finally, he left the loser crying on the Grange Hall steps.

Wanting to check on C.P. became a problem. My Model T was not quite the rig I cared to drive to a dance. Luck came when my neighbor sold his hired man, Gene Hatten, a great big, worn out, heap of a car for $50. My newfound friend got gypped, but he figured it was a lot of car for fifty bucks. However, it did come equipped with two flat tires, an extra radiator, and two whisk brooms.

Suddenly I had the feeling, while walking up to where all the excitement was, that there must be a better way to find your dream girl. The sound of music was pounding through the Grange walls as we opened the hall door. A drone of friendly chatter greeted our ears; perfume and a faint scent of booze greeted our noses. After fixing the flats and throwing the extra radiator out, we were able to make it out to North Star and find out what we were missing. Neither of us were ever at a dance before. We felt like a couple of lost sheep as we pulled into the parking lot. Noticing quite a few couples coming and going to their cars gave us the idea there were a lot of indecisions going on. (Was told later that some couples tire very easy when dancing.)

Not wanting the evening to be a complete failure, I thought it’s now or never to take my maiden voyage on the dance floor. Spotting a lady that I figured was built just right for a slow dance, I asked her and was able to hobble through it. That completed my initiation and we were ready to go home. We spotted C.P. sticking his neck around the corner, watching the happy dancers go scooting by. Naturally, we wanted to know what happened to his girlfriend. He told us he was mad at her because she wanted him to stay at her place for an evening of visiting. He could not stand a wet blanket. Saturday nights are made for dancing, said C.P., as he scraped the wax floor with his shoe that was on his longest leg. Not knowing what to say, my eyes started watching a couple I knew. I envied their assured enjoyment as they danced by. Soon C.P. poked me and said he was going back to the ranch because his crowd wasn’t there. The tiger, alias Windy Anderson, was actually a timid guy around that friendly crowd.

That fifty dollar clunk did the hesitation waltz all the way home due to a balky fuel line. The sun was getting ready to come up when I went out to the bunk house to check on C.P. — found him snoring; and by his pillow lay a True Story magazine. He must have fallen asleep reading it. (Years later I felt sorry for the guy. His fantasy world never came true. He was kicked around from place to place. A hard worker, a gifted fiddle player — but he was the darndest liar — and that made me nervous.)

Over four decades ago, to find Sugar, I traded off my Model A convertible, minus the side curtains, for a closed-up car with windows and the works. After some solo dance practicing behind the barn, I was once again ready for North Star Grange. Those lovely volunteer dance instructors at the Grange Hall were very tender with me. Soon I became good with my feet and body bounce. Later the tunes of “A Tisket, A Tasket” and the “Beer Barrel Polka” kept ringing in my ears long after the orchestra turned itself off.

Before developing enough intestinal fortitude to see if a Sugar existed, a couple of high school girls asked for a ride to the dance. Later their girlfriends asked to pile in too, and soon the names of Clara, Olive, Pete, Wyonia, Irene, and Theresa became familiar to me. This load of future wives always came home with me. They were just scouting around and I was their daddy-o. A mother figured that a four-to-one cargo ratio had some built-in safety features. So that left me with an image that I had to live up to. My duty was to get them all home safely in time for some sleep before church time rolled around.

In the search for Sugar, I just had to do some moonlighting between my Saturday night cargo. By vacating the car down to one passenger, I was then able to locate a Fayetta, then an Evelyn; thus proving to myself that I could handle dates.

The real break came when Bob Hardy found his Edna. That caused Bob to get married, and that caused the neighborhood to give them a shivaree. Wanting to see what a bride looked like spurred me to show up. After the traditional noise and destruction of a shivaree, and meeting Bob's brand new wife, I got to thinking that was no place to start a political argument, so I just gawked around, saying hello to everyone. All at once a smiling face met my face. It was Sugar. I thought to myself, "Could she be that stretched-out girl who not so many moons ago, waved at me out of the school bus window?" She sure did look different since all her equipment had arrived. I knew her when she was a timid little girl. Once I offered my knee to her as a chair, but she rejected me by walking away, carrying her doll upside down.

A week after Hardy's shivaree, we attended a high school carnival at Creston. In less than a month I took Sugar to a wobbly old justice of the peace and got married. A scary and a nutty thing to do, but I found my Sugar.

In 1889 the railroad missed Mondovi when it was building its way to Coulee City. So the town had to be moved down to where the railroad tracks were. According to records, when Mondovi became Mondovi there were only 16 humans inside that proclaimed spot. However, when a sawmill got going, the usual frontier buildings began to appear. It helped Mondovi turn

into a mini town. A blacksmith shop went into business mending broken rigs and farm equipment. The chop and feed mill supplied supplemental food for a lot of animals. A well cared for cemetery is still doing business on the outskirts of what is left of this burg.

into a mini town. A blacksmith shop went into business mending broken rigs and farm equipment. The chop and feed mill supplied supplemental food for a lot of animals. A well cared for cemetery is still doing business on the outskirts of what is left of this burg.

Mondovi gave me a place to be born in. Proud to say it was a decent village. Even though it had a saloon, it left no permanent effects on my dad during the time my newly married parents lived there. It had room for two churches, so you see it was a place more holier than average for a place of its size. Streyfeller, the famous old time Lincoln County preacher, got his start by preaching in Mondovi's Evangelical church. Later Streyfeller became converted to the Pentocostal faith. A well known Catholic family supplied the town with lots and lots of good Catholics. It was a tough place for a heathen to survive.

Practically all of our immigrant ancestors were quite religious. The countryside throughout eastern Washington was dotted with churches that were erected to satisfy their various inherited beliefs. Some still stand ghost-like, casting their shadows in the surrounding wheat and summer fallowed fields.

The Christians in those days may have been deeper into faith than the modern ones of today. To the early day believers it gave them special protection, something like being insured. When the law of averages hit them they drew on their policies and entered into eternal glory. Whatever happened, they couldn’t lose.

When I was a kid, churches took vacations in June. The faithful didn’t go tearing around, forgetting their religion for two or three weeks. They would set up headquarters in a grove of native trees. A spiritual tent would be set up about the size of an average modern machine shed. It was called “camp meeting time.”

Years ago, a scouting church member spied a grove of trees between Davenport and Harrington. It was made to order by nature, to hold a good-sized crowd. The oasis was blessed with a creek, a play field, and parking places for lots of family tents. The owners opened their arms and it became a summer paradise for the hard working Bible reading settlers. These June events didn’t fade into history ’til the middle 1920's.

Spring wheat was the main crop, and plowing was usually over with by June. In those days weeding was not practiced, so horses were turned out to pasture 'til the harvest days began to roll around. Everything seemed to work out just right for spending a couple of weeks at camp meeting where a free religious matinee and evening service were held each day. Those old faithful settlers didn’t really need a camp meeting for the purpose of getting their spiritual batteries re-charged. It gave them the opportunity to fulfill their communication needs by sharing verbal events with distant neighbors and having fun.

I remember that some of my relatives came from as far away as Ritzville. One clan even tied an old milk cow behind their overloaded wagon. It didn’t take long for the campground to fill up with dogs, wagons, kids, buggies, parents, tents, preachers and a good-sized scattering of unattached guys and dolls looking for excitement. Horn instruments were plentiful, and anyone who knew how to blow in music would toot out hymns. A vacationing minister would then wind himself up to last about an hour. Baseball was the main sport between services and wading in the creek was OK, even on Sundays. The busier farmers would only take the weekend off, filling the grove to the cracking point.

This camp meeting place finally changed denominational hands when the Pentecostal promoters from the coast moved in. Quite a few of my neighbors and relatives joined the new order, with the assurance of a more solid guaranteed trip on the road to eternal bliss. Although the friendly fellowship remained the same, it broke up the established churches into smaller pieces. Soon after, camp meetings faded from the scene forever. Later, different faiths supported special summer spots in more sophisticated distant places.

I’ve been questioned why I write so much about religion. Well by-golly, I’d be leaving a lot of local history out. At least half of my environment was and is spent in religious settings. In my lifetime more than a carload of my relatives got into the preaching business, plus several prophets were thrown in for good measure. A good sincere minister is of great value in any religious community. A lot of my best friends are sincere Christians. I happen to have a bad distaste for any evangelist that can’t stay out of trouble and takes advantage of the blockheads and the innocent ones.

Years and years ago, out here at Rocklyn, a lot of my Sundays were spent going to the Evangelical Church that was located a couple of miles south of Rocklyn proper. It was sort of a meek church that made us feel good to be Christians. My relatives and church going neighbors took it for granted that God was quite a guy and was full of love. We didn’t take the Devil too seriously ‘til the Pentecostals crashed the Rocklyn territory and preached the more scary parts of the Bible.

The invasion of this denomination caused our church to fold up. But it only shook the living daylights out of the Zion Church when it lost half of its members to the Pentecostals. Their camp meetings in Bursche’s Grove had powerful influence in religious thinking. Audio battle lines between the two factions were established.

It was quite a decision for some Rocklyn Christians to decide which faith to follow to insure a more safe and sure arrival to heaven. Sugar’s step-dad, Ed Deppner, chose the more complicated road when he joined the Pentecostals. To this day that fundamentalist church has been able to stand Ed’s onslaught of his unanswerable questions that he presents to their Sunday School.

The year of 1916, baby sitters were scarcer than hen’s teeth. My sister and I were only preschoolers. We had to learn to stay at home all day without the guiding hand of a babysitter. No, it wasn’t a case of child abuse. Our parents didn’t run off to some place like a tavern. Mom wasn’t well that summer. We were told that she had to be taken clear up to Spokane every week for treatments. I like to think that Sis and I were made out of the ‘right stuff.’ Most of the time, we did feel sort of brave. After receiving our weekly bye-bye hugs, we were left behind to witness the Model T disappearing in a cloud of dust. We would look at each other for a while, and then begin playing that we were at a camp meeting.

However, several times when we were left alone, ‘drop-ins’ supplied highlights, and some responsibility for Ethel and me. One long parentless day, in the midst of our play time, a bum came walking down the lane. He scared us enough that we sort of shook. The ice was broken when the bum asked if he could get something to eat.

Quickly we ran to the house. While sis was busy cutting up potatoes to fry, I was stuffing the cook stove full of wood. Dad always had a small can of kerosene to start the fire with. It’s a wonder we didn’t burn the house down.

The bum was fed a diet of fried eggs and a plate full of potatoes. After getting a free meal down his stomach, the bum left no tips.

Old Gus Kruger, a Rocklyn cattle farmer, was our weekly meat delivery guy during the summer months. Gus would knock a steer in the head, and peddle it to the farmers. The next week he usually would ‘do in’ a calf, so he could have veal as his speciality for the day. His Model T Ford held a shed like cabinet in the back that was full of fresh meat.

We kids were spending another day alone when Gus Kruger drove up with his mobile butcher shop. I told Gus I didn’t know what part of the steer to leave here. He said my mom usually wanted a roast and some steak. While Gus was setting part of a chopped up steer on a box, I told him I had no money to pay for it. Old Gus had a dry sense of humor which I didn’t understand. He thought a bit, then finally said, “If you promise not to eat the meat, and put it down the cellar ’til it’s paid for, I’ll leave it here.” Golly, that was a chore. Our old cellar hadn’t been used for a long time, as it was pretty well caved in. It took some time to get those two bundles of steer meat down that spider webbed cellar.

When the sky began to darken, sister and I always started to crave for papa and mama to return. When the stars came out, sis and I would manage to crawl up on the blacksmith shop roof. From there we could see the car lights as they came up over the creek hill. It was a disappointment when the magneto driven lights didn’t dim down for the turn off. It meant we had to wait on the roof for another pair of lights to pop up.

Eventually, a pair of car lights made it into our lane. That particular night found us running up to dad to let him know that Gus Kruger wanted the meat put in the old cellar, since it wasn’t paid for. Dad smiled, and said, “That sounds like old Gus. He was just having some fun with you kids.”

The folks always brought back goodies from Burgans Spokane store. Usually fancy, city-made, bakery stuff. Sometimes something wearable to brighten up our bodies.

In the fall of 1927 an inexperienced teenager saw pictures in a farm magazine where power from tractor wheels were being used for pulling purposes. An obsession hit him. He wanted a tractor in front of his plows, and other things, instead of horses. There was no way to be happy without a tractor. He talked his dad into mortgaging the farm. The half-size farm did have enough value to guarantee a 15-30 tractor. It was the biggest one International Harvester built at the time. It took weeks before it arrived on a flatcar.

One special day, there it was! A shiny new tractor sitting next to the Davenport depot. While dad was busy putting all the wheel lugs into the back of our old Essex, I was pouring water into the empty radiator. It took a lot of cranking before we found out there was no gas in the tank.

The tractor was steered down the road where it was going to spend the rest of its life. Before reaching home, Jack Telford flagged me down. He wanted to know if I really intended to farm with that rig, and what I was going to use for traction when the ground got soggy.

The next day, horseman Brandy stopped in to let me know that this tractor would be of some use back in the corn country. Butterfly feelings hit my stomach as lugs and rims were being installed to the tractor wheels.

The first job the tractor had to do was to pull some plows. It was quite a sweaty job steering around all those fence posts as the field was being opened up. Clumps of neighbors began to show up and were waiting by the starting corner of the field. They were wanting to see how the stubble was getting plowed without the aid of live horse-power.

After clutching the tractor out of gear, it was like parking in a group of critics. A ray of encouragement came over me when Herman Maurer said he wouldn't mind having a tractor like mine if he had all level land. The rest didn't think that way. "It will pack the soil too much," they said. Also, "It burns gasoline. Hay is cheaper." "If I run out of hay, I can get my fields plowed on stubble pasture." Fred Koch asked, "Why do you want to take on more farm expenses?" He stated he had to tear down his combine motor every season after averaging only three weeks of running. The rings and bearings were shot by then. In those days, good air cleaners were not invented yet. Homemade ones usually had to do. The Fred Koch Special was a gunny sack placed over the intake pipe. It did keep out straw, and other flying objects, allowing only clean dust to enter the motor.

Before the year was out, lo and behold, my tractor started making smoke instead of power! All that unfiltered dust had ground the rings down to a thin image of themselves. Even the lowest gear was too painful for the dusted out motor. The tractor did manage to limp back to the barn, where it was parked in the back stall for an overhaul job.

The partly finished field caused Quentin Maurer to ask why I took a vacation from farming. I don't remember how I answered that question. It must have been a vague one. After all, it was sort of a classified secret to save the reputation of future tractors. Later, an intake pipe was installed, reaching a height of eight feet above tractor height. A decent air filter was then bolted on.

Anyway, the seeds for future tractors finally got planted out here at Rocklyn. The next year Charlie Rux got antsy and swapped his string of nags for a Holt 30 tractor. Soon to follow was the Grob brothers. For a spell, the Great Depression checked the flow of tractors taking over the farms. Finally, when Roosevelt pulled the right economic levers, sounds of tractors could be heard in about every field.

Even as late as the turn of the century, if a guy took a dislike to his job and cried a lot, he could walk away from his depression. He could wander into the fresh air that was used only by a few early day settlers and still find a homestead. The soil that was left was usually on the thin side. Yet, if he was lucky enough to find a wife to share the joys and some hardships, all he needed then was a leather pouch half-filled with silver dollars and maybe a $20 gold piece. About the only way this typical couple could have gone broke was, if they did not use their noodles.

When I started updating my farm machinery in 1947, a new self-propelled combine was purchased for $3,900. In 1954, a second new one cost me $5,800. A new diesel wheel tractor was purchased in 1953 for $4,200. In 1958 was traded in for a giant of its time, for only $3,000 extra. For the two tractors and combines in my best 20 years of farming, I only had to pay $16,500 in cash. Using my renter for comparison, and this is just one of his farm items, this summer he bought a second-hand wheel tractor costing $40,000.

Ya sure, it does pull the same load much faster than my old tractor, and it has front wheel power to help lift its heavier loads over the hills successfully. It also came equiped with a cab where he can sit comfortably as he worries about whether farm conditions will improve.

Up to 1955 we farmers had a government guaranteed loan price of over $2.00 a bushel. From then on, 'til I tossed in the white flag in 1975, the price of wheat averaged $2.23 a bushel.

A sprouting, ambitious farmer, if he watches the market, can get about twice the price for his wheat than what us old ducks were able to average out, but you can't buy diesel for 19 cents a gallon, either. It would be a big help if the beginner was lucky enough to have married the farmer's daughter that happened to own a daddy who has faith in her guy. If not, the new future farmer will have to make a trip to the P.C.A.* office or some other place where he is taken for a 14% interest ride, while his landlord is collecting at least 11% interest on money market certificates. That's the way the capital system works. Kind of scary for the beginners, isn't it?

Our preparation for marriage, many years ago, took only from midnight ’til noon the next day. Digest version:

After taking Sugar home from a Grange dance...Sugar: “Don’t walk me to the house tonight, the folks may hear us.”Me: “OK.”Both: “Smack, smack.”The next 21 seconds, silence.Then Sugar: “Gee, I’m locked out!”Then me: “Golly!”Sugar: “What am I going to do?”Me: “Well, let's go over to my house and think things over for a spell.”Later, entering my pad...Sugar: “Now what?”Me: “Shall we elope?”Sugar: “I don’t care, I love you.”Me, (thinking to myself): "This is scary. Suppose Sugar turns out not to be a Sugar?"Sugar, (also thinking to herself): "How do I know he isn’t full of more things than just peanuts?"Me: “Do you know anything about sex?”Sugar: “A little, sometimes the conductor throws off a True Story Magazine, when the train goes by the house.”Me: "I have an outdated sex book, but it’s kinda for the birds.”Next day at Coeur d’Alene, a brother and sister standing on the sidewalk next to a marriage mill...Brother speaking: “Hi! We can be your witness for 50 cents apiece.”Me: “OK.”Brother speaking: “We will take you to Uncle Barton.”Entering a small room...Me: “I wonder if that wobbly old guy over in the corner will be the one that will marry us?”Sugar: “Not so loud, he may hear you.”Wobbly Old Guy: “I’ll be there in a minute. Have your license ready because I close at noon on Saturdays.”Uncle Barton went through the marriage vows so fast I had to be told that I owed him $2.50.

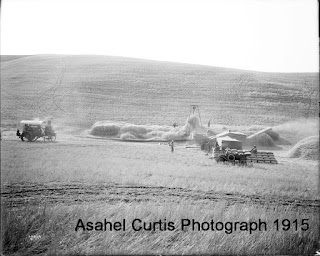

As a young lad I remember well what harvest was like in Lincoln County before World War I. This was before the glass enclosed paradise where a guy sits on top of a self-propelled combine pushing a few buttons and turning a steering wheel so that he can stay where the wheat is. It has been known in the Davenport area that more than 3,000 bushels has been laid away in one day by just one man, with the aid of a truck driver (sometimes maneuvered by just his lovely wife.) That adds up to just two people!

Now for a quick summary this morning while waiting for the rain water to get out of the grain so Sugar and I can get this crop out of the field. All that I saw as a young guy stayed as a photo in my mind. In those days it did take a lot of people help to get the crop into the hands of the buyer.

Take one year for example. It must have been 1914. Just as the grain was turning ripe, Herman Maskenthine’s outfit moved in and began what was called the heading outfit. Their job was to cut off the standing wheat and stack it for the threshers at a later date. A circle was started with the header in the center of the field, if you had a center. Our fields usually didn’t have one. The cut wheat stack was placed there for the threshers, which later set up a carnival of equipment to knock hell out of the wheat and put the grain into rows of sacks. Some heading equipment had derricks. If they did, the stacks could be made to look like huge round domed sponge cakes. Otherwise hand pitched stacks were made to look like bread loaves. They were usually placed side by side with room enough for the threshing derricks to be moved in between later. That year, the crew that it took to harvest my Dad’s crop consisted of the header puncher who maneuvered six horses in an odd way, straddling a steering stick, and the loader that sat on the header spout till another header box drove under him. Three header boxes, were employed each one requiring an operator, known as box drivers. Rather a skillful job.

The stacker had a derrick driver, usually a big kid eager to do a man’s job but had to take a lot of cussing from the stacker. And Irma, the heading outfit's daughter, had to be called a helper, as she helped Mom shell peas and get dinner ready for the heading crew. Just to get the standing grain sawed off and put into a heap, it took eight people, plus Mom.

Next, after a few weeks, came Mike Maurers threshing outfit. I wish I could take the time to explain the equipment piece by piece. It was a romantic harvest scene. As a kid I thought dreamily, how I wanted to be a steam engineer and pull those levers and whistles with such authority and keen knowhow. Otherwise, he didn’t seem to have much to do but sit on a shelf near the throttle levers in case someone waved to stop the works. Now recalling, it took one engineer and the fireman to run the thresher. I believe the fireman was known as the fellow who hauled the straw from the straw stack with a cart, back to the engine to be shoved into the fire box for making the energy. Some had a guy hauling water if the supply source was farther than over the hill.

To feed the stationary separator from the setting, it took two men each operating a Jackson fork that dragged a large forkfull on a large flat table that was built on wheels - two fork drivers. From this table four hoedowners used a fork that was mashed into a 90 degree angle, making it into a sort of a hoe. The four guys worked in pairs, pulling the unthreshed wheat into a Jackson feeder that fed into the cylinder, with the other two changing off every twenty minutes because they were pooped.

Then there was the separator tender. He always looked busy, moving his eyes and walking around with an oil can. As the grain came out of the long spout, a guy that was called a jigger was at work. He put the sacks on the spout and bounced them up and down to get more wheat in them. Then he sort of handed the filled sacks to the sack sewers. There were usually two of them and they had to buck them into long rows of stacked sacks. (If there was no bucker.)

Usually the outfit had a “flunkie” but he never cared for his title. Sometimes a straw stacker was hired; I remember I used to watch one. He had a face full of whiskers, and was continually trying to wipe the chaff out of his beard. It seemed like the straw blower and his face always were pretty close together.

In the case of our operation, there was no cook house crew, so it was up to my good Mom with the aid of my aunt to feed the mob.

Now if I am right, that totals to around 13 for the harvest crew, eight to put it where it could be threshed - a total of 21 men. And the wheat was still nowheres near the warehouse. That was the job the farmer himself had to do during the long, strung out days after harvest. Since I scribbled out this article for Sugar to type, I think I’ll go out and see if it is dry enough to push the starter button and get to harvesting.

Not too many years ago after my renter, Gene Stuckle, was born he became interested in just about everything that was mechanical. Later, Gene transformed his ability to turning deteriorated old cars into antiques - but that’s another story.

When this “on-the-go” feller plunged into farming on his own, he turned into a hopeless antique tractor restorer. He actually hunts for these discarded power plants with his binoculars, either at ground level or looking down when he is up in one of his planes. Anything resembling a rusty old iron horse is checked out for graveyard release. Gene, now, has many a deceased old tractor restored to life by adding transplants from hopeless basket cases.

Seeing Stuckle’s collections reminds me why I decided to tractor-farm after arriving back from California in the fall of 1927. Full of dreams of farming with horses fascinated me. The thought of commanding lots of horses, western style, made me tingle. Buying a cowboy hat and sticking it on my head got me into a lot of trouble. Veteran farmers thought I knew everything about horses. Putting a fresh pair of leather gloves half way in my hip-pocket didn’t help matters either.

Anxious to get some plowing done that fall without investing in a string of nags ’til spring, I asked my cousin if I could use a gathering of his horses so a three-bottom plow could be pulled. I was told to take the saddle horse and round up a group of work horses that were out in the pasture. Like most riding horses, this one had three shifts of speed. First, was a horse walk too slow to scare any of the work horses back to the barn. Second, was a jolting trot. It kept my cowboy hat on OK, but it didn’t do my seat any good. Since a gallop was too scary for me I just tied the thing up to a fence post and shooed the horses back to the yard.

I tried to help cousin Quentin get all those nags dressed up in their working outfits. There were odd names for different things that went over their bodies, so they could deliver their horse-power. Some were understandable, like belly-bands, as all horses had bellies. The tail piece naturally was for the tail, collars for neck, etc. Quentin did show me how to tie or hook up the whole 11 horses to the three-bottom plow, which didn’t come with a seat, only a plank to stand on which was wedged between the plow-beams. Quentin pointed and told me the names of every male and female horse as he handed me the lines. Even a written instruction sheet wouldn’t have been of any help. Everything seemed so strange.

Before I was able to stand correctly, Quentin yelled “get-up!” Those words started the whole tribe moving, and the plow began to plow. Luckily those horses of all ages knew what they were doing. They did start turning on corners a little too soon. It was impossible to figure out how to tell the herd to go just a little bit farther, without throwing all of them into a state of confusion.

The next day, the plow struck a rock, causing me to end up in the furrow. Luckily, the horses worked like a snowmobile and stopped when the driver gets tossed off. Later that afternoon, the plow really did a good job of bucking me off, landing me on my head and shoulder. That did it! My mind got made up to trade that twisted brimmed cowboy hat in for a beret and to work on my dad to hock the farm for some money that would buy a tractor.

Before spring work started, a 15-30 International wheel tractor, the biggest one the company made at that time, was standing on a flat-car in Davenport, waiting to be unloaded. Driving it out to the farm was a thrill. Going past Paul Jahn’s farm gave me a feeling of security, as he had already started farming with a Twin City tractor. From then on west, I was invading horse country and I tractor-farmed happily ever after.

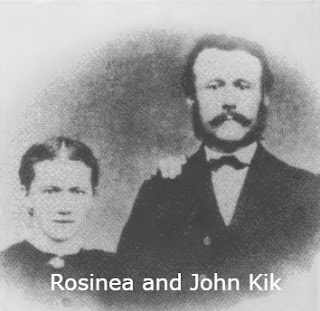

Let’s go back to Germany in the spring of 1872. A guy by the name of David Kik, Sr. ran off with the baker’s daughter and beat it to America. Grandpa did not want to serve in the German Army, as he had no desire to learn how to kill people. He and his brand new wife got on a sailboat so they could be blown over to New York.

Yankton, South Dakota, was the first test for these newlyweds as they staked out a homestead. After five years and a few babies were born Gramps started to get bugged when he saw what the grasshoppers were doing to his crops. He found a guy that didn’t mind grasshoppers and sold him their farm. He then decided to take his family to Los Angeles to see what 10,000 Mexicans and about 500 white settlers looked like. Hot weather and cactus wasn’t their bowl of cherries.

So Kik piled his family on a schooner that was headed for the Columbia River. Gramps then bought a team of Arabian horses named Kitty and Sally, and hooked them to an overloaded wagon and then headed north. His only protection and food-getter was a double barreled, muzzle loader shotgun. Why it took grandpa six months to get up here to Fort Wallula, I never did know.

When he pulled up to Wallula, he found his brood sitting and waiting for him. Gramps also found his wife very heavy with child. This one was going to be number five. They all found a haven for the coming winter with the George Minkles. Grandpa no sooner got his legs stretched out from his long wagon trip when grandma gave birth to a baby girl. The cold winter wind whistling through the Minkles’ single-boarded shack didn’t help any. She died from child birth and was buried at Wallula’s Army Cemetery.

An article in the Walla Walla Journal, dated Dec. 15, 1879, read as follows:

“Some time ago we gave the painful news of a poor mother dying at Wallula, leaving a husband with five small children. Since then the father found homes for two of the small ones. Dr. Clowe of Walla Walla took one of them. Mrs. Thomas Collins took the baby. Mr. Kik, an immigrant, lost all in coming here, even the mother of his little ones.”

The spirit of Christmas didn’t even try to raise its head at the Minkles’ cabin that December day.

When the spring thaws had set in, Dr. Clowe told Grandpa there was lots of good land north of Sprague that the government would just love to give away. The Minkles offered to take care of the third youngest child, while Grandpop loaded the two remaining kids into his prairie schooner along with his earthly possessions. Arriving at Sassin he found Mr. and Mrs. Delius Woods who had already staked out a claim. At the mercy of the Woods he dumped off my dad and his sister and went looking for land. The claim on which he filed was well chosen. The gentle hills were just made for farming.

This 160 acres of land was called a preemption. It cost grandpa $250 but he had 10 years to pay for it. A timber claim was taken for another 160 acres. It was free, but the government made him plant 10 acres to trees.

After squaring up with Uncle Sam he got his axe out and chopped down some stray pine trees after which he made himself a one-room, one-door, one-window log house. Then dug a hole deep enough to make a well. Then Grandpa put on his coat and got ready to pick up his five scattered children. Kitty and Sally then had the job of toting Gramps and his wagon back to Walla Walla.

Dr. Clowe wanted to adopt the son he kept and it sounded like a sad parting of the ways when the youngster was tossed into the wagon. No trace could be found of the baby girl nor of the Collins family. Rumors were that they moved to Yakima. So when grandpa got to Wallula he fixed Kitty into a saddle horse and road to Yakima. Neither the Collins', nor the baby could be found.

Kitty and Sally finally lugged Kik and his two remaining kids back to Sassin, where at the Woods’, grandpa picked up kids number three and four. All he could offer the little ones was a log cabin with a window from which they could look out. That’s just what they did that fall, when he locked them in the cabin while he took four sacks of wheat to Gunning’s Mill at Minnie Falls, where a small water-wheel ground it into flour.

Kik and his waifs were the first Germans to arrive on Rock Creek. The Irish beat him there. They included the Murrays, Brislawns, Belfrys, McCafferys, Woods and McGreevys. The farming type of immigrants started pushing into Edwall country soon after, and included Mielkes, Polenskes, Krones, Scheffles, Kintschis, McPhersons and the Minkles, from Wallula.

Santa Claus came a few days early that year, when Dr. Clowe sent an old prospector on a horse up to Kik's cabin, with four red tin horns and a large jar of horehound candy. The Krones made it possible for Kik and his brood to have their first real Christmas. Kitty and Sally pulled a sled-load of excited little ones through a wilderness of snow. When the Krones’ cabin came into sight, their father told them to blow their red horns. Blow they did. The horses ran away. The sled turned over, breaking a runner, and the little ones landed in the snow. Their father spent the rest of Christmas day trying to catch Kitty and Sally, while the children walked to the Krones’ house.

“When we walked in,” my dad told me, “we smelled pork sausage frying. I’m sure that I never in my life have smelled anything as good as that meat cooking. To this day I often think of that Christmas long ago, when we entered the Krones’ cabin for Christmas dinner. Mrs. Krone also served sourdough bread.”

The old double-barreled muzzleloader was put to high use that winter at Sassin. When the children got tired of eating sage hens, grandpa would aim his shotgun at some jack rabbits. After Christmas, a cow was rounded up from somewhere, and wheat was boiled for breakfast. For light, potato candles were used. These were made by carving a hole in a raw potato, then filling it with grease. A stick that had been wrapped with a rag was stuck into the spud; it was lit by a sulphur match.

Boy, it sure was a blessing when spring came. Out of cash, Grandad got a job staking out claims for the government. When he was gone, he turned his children out in the yard. The cabin worked as a brooder house. During the first two years, he would drive down to Walla Walla for supplies and to pick up his mail.

Later, Colfax became the trading center. During this period, his children invented a language all of their own. I was barely able to swallow that yarn, until I heard my dad and his oldest sister carrying on a conversation in their non-patented language. Long after, a schoolhouse was built and these secret coded youngsters used their gibberish for private conversations.

My pop and his brother had the honor of setting the largest prairie fire known, for their size and age, wanting to burn out just a small patch of dry bunch grass so Kitty and Sally could have some green dessert to chew on. Those two did have good success in starting the fire but stopping it became too much of a problem. The boys took their pants off and tried to whip the fire out, but the pants proved to be a poor substitute for a fire engine. The prairie burned a ten mile wide swath on it’s way to Medical Lake, where it stopped by itself. Not wanting a licking, they told their dad that the devil came out of the woods and set the prairie on fire.

As time passed, Grandpa was able to get quite a bit of the virgin soil turned over. After five years, the children’s growth left less space between the beds and the table, so he nailed a lean-to on the log house.

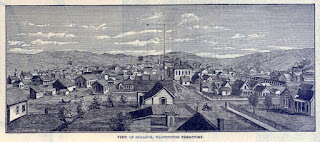

By now the railroad was pushing itself out West. The company’s brains in the east picked Sprague, instead of Spokane, as a place to fix their broken-down steam locomotives, so that called for the construction of round houses. Sprague was fast turning into an exciting frontier town.

Young ladies that wanted to leave home were hired by the railroads to work in their company’s own restaurants out west. Louisa Rux, a young lady from Minnesota still in her tender teens, beckoned to the call of the railroads and got a job as a waitress in Sprague. Gramps, on one of his many trips to town, spotted Louisa, and soon started having chow where she worked. Beings this young lady was 24 years his junior, he had tough sledding for awhile. Finally she accepted his proposal. It seemed strange why she wanted to leave all the glitter Sprague had to offer at that time and exchange it for a middle-aged guy with four rough-necked kids and a cabin with only a lean-to.

Grandpa went on a big “high” and threw one of the biggest wedding celebrations I ever heard of. By this time a lot of future farmers had settled around the Kik place. A dance floor was nailed together near the house for the wedding party that didn’t get turned off until three days later. The neighbors furnished the food, but gramps had to kick through with the beer. That seemed to be a must in those days. All of the young folks that attended the celebration became lasting friends. Later, the Kleins, Kiks, Bursches, Ruxes, and the Fritsches intermarried and became one clan.

Grandpop was so happy about his conquest, that he invited his bride’s family to come out west to the promised land. That fall the train had a train-load when old man Kik’s in-laws pulled into Sprague. They brought everything with them except the farm. The human cargo and all of the valuable stuff filled up half of a passenger car, which included Carl Rux, his wife and five offspring. The cattle rode in a corral-like car with a roof on it, followed by three flat cars full of farm machinery.

There were no vacant houses standing around in that vast Edwall virgin territory, so the Ruxes were willing to semi-hibernate with the Kiks for the winter. The seven piled in with the six cabin dwellers. Privacy went out the window that winter. A let-down ladder made it possible for all the boys to sleep up in the boarded-up rafters. For Christmas, the young folks made their own play money out of scarce slips of collected colored paper. The rare purple color had a highly fluctuating value. This legal counterfeit money was divided evenly among nine juveniles. Charlie, the whiz-kid from Minnesota, became a capitalist. He owned a jackknife and was able to carve out toys and sell them to the rest of the children. Inflation ruined their money when a flood of colored paper found it’s way up from Sprague.

While the winter winds were howling outside and the children were raising hell, old Grandpa and his father-in-law were planning for spring and making verbal deals. Machinery was scarcer than hen’s teeth. Anyone bringing farm machinery from the east had it made. Grandpa was more than willing to trade his 160 acres of timber claim to his father-in-law in exchange for his header, his chopmill, and a set of harnesses.

When the spring of 1888 rolled around, the Ruxes were able to build a farm of their own. The next year the scattered settlers built a small schoolhouse. Lydia Hemmersmith, who only had a fifth-grade education herself, was the first Sassin school teacher. School days only lasted for three months a year, causing happy vibes among the pioneer children. My pop’s oldest sister never went to school. Dad was 12 years-old before the schoolhouse was finished enough to open its doors. He quit when he was in the third-grade. Having to shave was an embarrassment to him.

Not too many moons passed when gramps started up another batch of children from his second wife. After expanding his land holdings by moving to Rocklyn, he up and left his second wife by dying of cancer at the age of 50. Grandpa probably promised her a rose garden, but all he left his 26-year-old wife was an array of little ones to raise. For survival, her stepchildren found employment or got married. With a restless dream of looking for something better, many pioneers around here reached their goals. Grandpa did not. I still believe he tried.

A long time ago farmers had to creep before they could walk. When 1939 rolled around, the price of wheat had doubled itself from the rock bottom price in 1932. Even with that 100 percent price raise, wheat was still selling for less than a dollar. Yet, a bushel of wheat bought more stuff 46 years ago than it does now. In some ways farmers that were broke then, were in much better shape than the speculative farmers that are in debt today.

In those pre-war days a lot of us farmers didn’t have much money in our pockets but it didn’t cost anything to wait for better times. When 1942 showed up, wheat was finally needed and inflation stood still for a long period of time due to a government price freeze.

In 1939, when I was broke, I happened to develop a strong desire to get married due to a good opportunity that I was faced with. Not wanting to wait for my government allotment check to come, I borrowed $25 from my brother-in-law so I could get my act going. That twenty-five bucks made an elopement possible, also a three day honeymoon, Spokane style. In those days it wasn't the 'in thing' to shack up with a new-found Sugar to see if we were made for each other.

Since I spent time exploring Spokane during my single days, I knew it offered a girl that lived a sheltered life all the necessary entertainment to make her honeymoon a memorable one. By handling the borrowed $25 just right, I knew it could be done. That Justice of the Peace and that poor man's bridal suite at the Cour d'Alene Hotel took quite a chunk out of our spending money. Our wedding picture came to 25 cents. Payless Drug Store had a self-taking portrait booth with a curtain for privacy. When we thought that we looked just right, Sugar pushed a button. After a happy hug or two the picture came out of a handy slot.

Our wedding dinner consisted of a brisk walk over to the Washington Street Market where a Dutchman and his wife served a plate of full dinner, including soup and pie, for 25 cents. There was a cover charge of five cents to have a scoop of ice-cream dumped on Sugar's pie.

Since Sugar never saw a stage show, it was pure luck that Sally Rand was in town and performing on the Orpheum stage during our honeymoon. Sally's body and her bubble put on an artful show, for which she was famous. The glitter and beautiful stage lighting, as well as the loud music that the Orpheum's orchestra blared out, overwhelmed Sugar. The next day was more of the same, except window shopping was stretched out a little longer to take care of our fantasies. On our last afternoon in Spokane we called on Sugar's aunt Susie to see how she would react to our sudden marriage. She didn't give a darn what we did and told us to sit down to a bowl of her Polish-type of potato soup. After paying what we owed for the use of a hotel room I found out there was enough money left to buy a box of smelly cigars. We took it for granted that we were going to be shivaried when we got back to Rocklyn. Guess it was just lots of luck, love, and tender care that we made a go of it for all these years.

My dear mother, Margaret, was born and partly raised in Russia on a wheat farm along with other peasants. Her parents had a large amount of sons and daughters. Lacking room, they came to America. The family first settled in North Dakota where they built a sod house because trees and lumber were scarce as hens teeth.

In a couple of years, Daddy Rieker heard the call of the open west and moved his family to Walla Walla. From there, the grown ups started to spread out to other Germans-from-Russia settlements. One brother, Christ, started farming around Ritzville and later took over some of the business buildings in Ritzville and became citified. Mom’s oldest sister, Kate, was married in Russia. That couple made a beeline to Ritzville where lot of brand new land was waiting for them to farm. Brother Jake settled in Walla Walla where he grew an orchard and built a packing house where lots of apple packing took place in the fall. Another brother, Gotlieb, took the spiritual road and became a Congregational preacher. He got stationed in lots of towns in the Northwest. Sister Lena, found a husband that was glued to Walla Walla. They raised a lot of fruit and vegetables for anyone that cared to buy fresh stuff. Sister Caroline married a guy that caused her to have twelve [children]. That family helped propel the Seventh Day Adventist movement around Walla Walla and up in Canada where they also did a lot of wheat farming. Mom just stayed in Walla Walla attending church functions and picnics in the Blue Mountains—until Dad got in the picture and married her and took her to Lincoln County.

Before I became a gleam in my father’s eyes he darn near flubbed up my chances of ever being related to this special stock from Russia. As a young guy, while courting my mom down at Walla Walla, Pop asked Gramps for Mother’s hand and blessing. Grandpa asked Dad if he was a Christian. Pa told him he was "a damn good Christian." This paraphrasing of the type of Christian he was caused Pop to tumble from the old man’s grace. Love letters had to be rerouted to Grandpa’s neighbor, who happened to understand Cupid’s intentions much better.

A fairly large percentage of the early day young men took the opportunity to find out what life was all about on the other side of the fence. As far as anyone seemed to know, the only drugs that were around in those pioneer days came in liquid form and were readily available in all saloons. The toxic dope, tobacco, usually was used by our ancestors in the less harmful form to get their kicks; such as pipes, chewing tobacco, and big fat cigars. They even stuffed the stuff up their noses.

When homemade cigarettes came on the western scene, there was a certain amount of pride in the cowboy’s ability to roll his own cigarette while his horse was trying to buck him off. Factory-made cigarettes were generally smoked in those days by city dudes and the more classy prostitutes. Sure, a lot of those early generation young males kept their noses clean, mostly due to stricter environmental conditions. Those that didn't usually were of no worse quality than the meek. After a little taste of sowing their wild oats, they sought a level of life according to their inherited ability, and became some of our best known Lincoln County citizens. In 1892, a couple of 15 and 16 year old lads from the Edwall area were fast turning into young manhood. They had already been initiated in the grown-up world of sinful smokers by getting sick on a mixture of dried rose leaves and raw tobacco. They used a clay pipe as their pot machine.

After harvest, old man Kik loaded 20 sacks of grain on a wagon. He told his boys, Dave and Charlie, to haul the grain to Spokane to sell it to a livery barn. The money was needed to pay taxes. Anticipation ran high when their stepmother packed a large lunch. Noontime the next day the small town of Medical Lake found the boys resting the team and eating their lunch. Darkness came before the 20 sacks of grain were driven up to the Mission Livery barn in Spokane. The brothers slept under the wagon while the tired horses chewed away all night, converting hay into energy.

When morning arrived the teenagers received a $20 gold piece and four silver dollars for the load of grain. After downing what was left of the day-old lunch, temptation caused the boys to wander around the tinsel side of frontier Spokane. Late that afternoon when hunger came over them, the brothers ordered a couple mugs of beer, which would have entitled them to all the sandwiches they could eat. Because their faces looked too slick to be old enough, they got kicked out of the saloon. A quick check of their trousers revealed they still had the $20 gold piece, but nothing else. Fright set in, so they beat it across the river to in-law, Jacob Klein’s place. At supper time a good meal was devoured and later the Kik lads were blessed with a safer place to sleep. When morning broke the boys were letting the team take the wagon, themselves, and the $20 gold piece back to Edwall.

Like a lot of pioneer families, things didn’t always turn out the way dreams were planned. The following year, (1893) old man Kik died, leaving a farm at Edwall and Rocklyn, a string of youngsters, his second wife, lots of problems, and a transition period for the two oldest boys. Events and lots of work made time not available for Dave and Charlie to leave home, since the Spokane Falls wagon trip. When the stress of family problems started to level out, Spokane, again, entered the boys’ minds. They managed to save some money of their own, so they could satisfy a desire to purchase full-length, adult, dress-up suits. These teen-agers had long since outgrown their old model “Sunday” pants, with trouser legs ending at the knees. Those outfits were called “high-water pants” because wading in creeks could be done without getting the pant legs wet.

Eighteen-year-old neighbor, Max Mecklenburg, had the same idea and joined the 16 and 17 year olds on their first train ride in the pursuit for new suits. It didn’t take them long to scramble off the train in Spokane and to locate the I.X.L. clothing store on Riverside. The suits averaged the young guys $10 apiece. For accessories, Charlie laid out three bucks for a “solid” gold-plated watch that had a long chain; Dave, a fancy stickpin for his tie; and Max, a pair of patent leather shoes that never needed polishing. A barber shop took care of their faces and excess hair. When the three young lads figured they were all fixed up with the right equipment, a walk across the street from the barber shop took place. An arcade type of photo studio was located there. When an image of themselves was recorded, the guys rented a three-cot room located above a saloon. Then they were ready to investigate the town.

Now these young fellers didn’t know that Spokane had some hidden spots where society was in a scholarly pursuit of fine arts, and other educational things. In those days no weekly cultured magazine ever found its way to Lincoln County. On the other hand, if Madame Scheuben Hite happened to have been singing at the well-known Spokane Auditorium, I doubt if it would have been on the boys' minds to attend.

The stars were out by the time the newcomers started to go sightseeing. Farther to the east, noise and music was coming out of the Stockholm Dance Hall. Automatically, the three walked in. Max could bluff his way around real good. The brothers caught on and followed suit. It didn’t take them very long to work their way past the bar and dance hall, then into a theatre-like room where risque acts on the stage were in process. Three seats in the front row were taken by the lads in brand-new suits. The show was free, but they were supposed to buy beer and “other things” it had to offer.

What my dad and the other two rookies saw was quite a contrast from life at the fatherless farm home. For example, if his stepmother had her sleeves rolled up during bread making, she would roll them down before answering the door. The stage girls didn’t have any sleeves to roll down, nor long skirts to cover their legs. Between stage acts, beer rustlers would go up and down the aisles, selling mugs of foamy stuff. For a price, they could have gotten a private booth to watch the show from and a dance hall girl thrown in for company. Although dad strongly advised against gambling when I came on the scene, he did fall for the "Las Vegas" lure of early Spokane. It caused a share of his spending money to disappear.

Those darned guys (the brothers), never realized that fate was waiting for them to settle down. A cattle ranch was waiting for them at Sprague Lake. Homesteading had to be taken care of. My mother was still to be found and courted. Not yet interested in the future, Dad and Charlie got the ‘Spokane itch’ for the last time in the fall of 1894. Gus Rux and Henry Derr had planned to take in Spokane with them, but chickened out the last minute. To save some silver dollars, the two wild ones decided to beat their way to Spokane. This was done by jumping on the cow-catcher of the Great Northern train engine, when it started to puff away from the Harrington depot.

The odd ride came to an end just east of Edwall when a cow was hit. The scooped-up cow caused Charlie to get a broken leg and lots of bruises. The train didn’t stop, so when the boys crawled back to the cab, the engineer said, “Did I run into a schoolhouse?” When the train pulled into Spokane, Charlie was taken to the Sacred Heart Hospital, with Great Northern paying all expenses. Later, a trial resulted when the farmer got peeved and sued the railroad for the sudden death of his cow. The boys again got a free ride to Spokane. This time in style, inside where it was warm and not so windy. The Great Northern needed them as witnesses because they had a good view of the cow’s final moments.

(How did I get all this information? Easy. Years ago, with an old wire recorder running, I asked Dad a lot of questions of his early day escapades in Spokane. This winter, on a snowed-in Sunday and for the want of something to do, I played it back.)

Once upon a time, in the early dawn days of Sprague, Washington, two male orphans in their late teens joined [as] partners with Jack Muench in a cattle and horse ranch venture. Muench at that time owned lots of rocks, sagebrush, tullies and bunch grass land that was connected to Sprague Lake. As time passed, calves grew into cattle and colts became horses. When dividing time rolled around, the owner of this ranch didn’t share the same viewpoint on a verbal agreement with his two junior partners. An exciting court trial at Ritzville did give these two young men their just share of the livestock. The verdict caused the owner to see red, so he kicked both of them off his property. They had to look for a place to park all their cattle and horses.

The year 1900 found the government still wanting to give away lots of land south of Wilbur, in the Lake Creek country. Just the opportunity these two brothers, Dave and Charlie Kik, were looking for. Johnny Harding, a Sprague lad, decided to join them on their road to new horizons. The three young fellows managed to get the herd of animals up to Portugie Joe’s territory. While the cattle and horses were looking over the many lakes, and having a field day eating their happy way through belly high bunch grass, the three guys were busy sampling different spots to homestead on. They eventually found a high ridge that was full of good soil. It had enough room on it for each to have a 160 acre chunk of ground.

Before winter showed up, three crudely built shacks appeared about a quarter of a mile apart at skyline height. Each had a stove pipe sticking out to one side. Late that following spring the land was turned upside down and later wheat was planted on the buried bunch grass. Brand new neighbors began to appear to the west on what was called “Russian Ridge." This gave the three guys a chance to swap with the immigrants. A lot of cayuses were exchanged for a communally owned heading outfit.

An idea was fast being born in those bachelor minds. Why not become the harvesters in that isolated spot? But that was hard to do without a thresher, so up to Wilbur they went. M. E. Hay had a store that held about everything homesteaders needed. The three new farmers browsed around for awhile at this farm equipment shopping center. Since they were horse lovers, they bypassed the steam engine. Finally they ordered a horse-powered threshing outfit. All these fellers had to do to take delivery, was to sign a piece of paper stating that, after harvest, enough money would be delivered to satisfy the agreed sale. (Old Hay was a trusting old soul, wasn’t he?) Later, the whole works was towed out to their newly granted government land. After setting up the array of equipment they realized a first class chow house on wheels was a necessity. A wagon running gear was stretched out to the limit and that became the length of the restaurant on wheels. A liberal supply of foot boards, two by fours, and a bucket full of nails was all it took to build their cookhouse. The word “cookhouse” was then painted on the raw wood over the main entrance. A wooden water barrel and a cook stove were installed. They nailed together a table that extended down through the center of this eating house.

Johnny Harding knew of widow Dare down at Odessa and her teenage daughter Julia. By communicating on horseback, the two women were hired as harvest cooks. No room was provided for their privacy. They had the choice of sleeping on the cookhouse floor, or under the cook wagon. For everyone, the wide open space was their toilet. The men usually bedded down in the straw stack. The outdoor utility room was the outside corner of the cookhouse, next to the strapped on water barrel. Before mealtime, the headers and the threshers would wash their dusty faces in pans that were strung out on benches. A couple of five foot lengths of towels hung on spikes driven into the cookhouse.

I was told, when the cooks arrived, supplies were just stacked up in the cookhouse. It was up to Julia and her mother to use their skill to turn flour, potatoes and the more solid forms of food into edible stuff. Kentucky fried chicken and home ground peanut butter weren’t around in those days. Fresh meat would have gotten over-ripe fast in hot weather. I suppose a lot of salty ham passed down the harvesters’ throats.

The large crew was well-pleased with what widow Dare and her daughter dished out. Sugar, (the other kind) made a lot of things taste good, like cookies and apple pie. They had to get up before the crack of dawn to boil a lot of oatmeal mush, and crack lots of eggs into frying pans. The crew always started heading and threshing about the time the sun got up with the morning.

Despite all the hard work, hormones among the group stayed at normal levels, so flirting between the eligible men and cooks went on the same as it would today, but in a more bashful way. Julia had a way of showing favors by giving some of the men a slice of apple pie with their mid-afternoon sandwich and coffee break.

(To be continued...)

mondovi cut

Every settlement has a heritage tale of some kind to tell. Mondovi is no different than any other place. True, old time events are slanted to what one knows about the past.

So now let’s start off by heading east of Mondovi for a five minute walk down Railroad Avenue. There, to the left, lived a guy by the name of George Betts. He had a farm but needed a wife, so he married my Aunt Lou. George, then, built a fancy home. He came from an inventive family, so he built a factory like shop that was powered by the wind. Shop holidays were when the air stood still.

Having no control over a fatal illness. George Betts died, leaving behind a practically brand new wife. My aunt then picked for her second husband — a gambler and a rounder by the name of Jack Smith. Being full of faith, she had plans to reform him. Finally Auntie Lou realized husband number two had no desire to look at the hind ends of horses all day long while doing field work so she sold the farm to my dad.

We will now drift back into Mondovi proper where in 1896 a couple by the name of John and Susan Zeimantz contributed considerably to the population of Mondovi by raising ten children there. Eight girls and two boys — a lopsided figure that helped balance out a male dominated population.

John helped support the family by working for the Puget Sound warehouse in Mondovi while his wife ran a boarding house on Main Street. During the peak season she fed up to 20 hungry workers, family style, for 25 cents a meal. Poor and unspoiled, the rapidly maturing off-springs pitched in to make survival possible. Something like the Walton family on TV.

Community life provided this town’s entertainment. On Sunday afternoons the passenger train arrived from Spokane with a supply of mail and a stack of Sunday papers that sold for 5 cents. Folks would drive into town and tie up their live transportation so they could socialize with friends and neighbors. By the time the crowd reached it's usual size the locomotive smoke could be seen in the distance.

A special event would come to this burg when a one-man traveling show showed up. King Kennedy made annual appearances at the schoolhouse with his Punch and Judy show. King could make those rag dolls talk in a ventriloquism fashion to the amusement of bug-eyed youngsters and fun-filled adults. The Zeimantz children all got free tickets to the show in exchange for supplying boarding house meals to the man that could throw his voice.

The Zeimantz teenagers were a friendly bunch. Regardless of their inherited faith, attending a Protestant church was no sweat. They got to see a cross section of life in an early-day town that never grew. Eligible bachelors came in various sizes and professions. Among the wife seekers, competition ran high for the attention of the Zeimantz girls. Even their names sounded attractive: Mary, Gertie, Irene, Sophia, Minnie, Lena, Susie, and Margaret.

Before marriage, my dad was stuck on Gertie, but events didn’t jell. After marrying my mother, Dad forgot to take the picture of Gertie off the dresser top. Upon returning from their honeymoon Mom wanted to know what the picture signed “With Love” was all about.

Mother, coming from a tightly knitted German-Russian background, felt lost in the mixed society village of Mondovi. By the time I got born, the Zeimantzes made mother feel right at home. So much so, that mom hated to leave Mondovi when migration started us back to Rocklyn.

Years later, who was the first to get to see our brand new day old 1916 Model T Ford? - the Zeimantz tribe. Without any driver’s training Dad was able to steer the Ford to Mondovi with only two rest stops. A 13 mile nonstop trip got us back home that evening.

Comments

Post a Comment